A group of political heavyweights from yesteryear wants the United States to introduce a carbon tax to help cut greenhouse gas emissions. Surprisingly, they’re conservative Republicans. Unsurprisingly, airline trade associations aren’t interested.

Including a corresponding carbon dividend for Americans, the plan comes from the newly launched Climate Leadership Council. Former cabinet members James Baker, Henry Paulson, Jr., and George Shultz are among the co-authors. They helped publicize the proposal last week and now are pushing the Trump Administration.

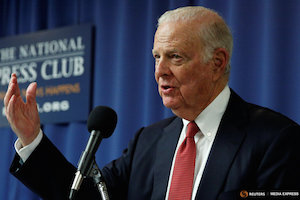

Economist Martin Feldstein also is a co-author of the proposal. Last week at the Climate Leadership Council’s kick-off news conference in Washington, he explained how the tax would work: “Require each household and each business that causes carbon dioxide emissions to pay a tax in proportion to the volume of emissions that they create.” The tax, Feldstein continued, “would be levied indirectly by taxing the raw material at the point at which it enters the economy.” For example, oil would be taxed at the refinery, or at the port where it enters the country. “The tax at the source,” Feldstein said, “is then built into the prices of the products made from that raw material.”

In a January 2017 white paper, Climate Leadership Council founder and CEO Ted Halstead wrote that the tax would be “passed on to consumers in the form of, for instance, higher gasoline prices, airfare and electricity bills (depending on your source of power).”

Image: Reuters/Kevin Lamarque

The tax would start at $40 per ton of carbon dioxide and gradually increase.

It would “send a powerful market signal that encourages technological innovation and large-scale substitution of existing energy and transportation infrastructures,” according to the proposal.

For businesses, the idea is to create an incentive to use more fuel-efficient technology. For airlines, think new-age airplanes and biofuels.

Because tax proceeds would go to Americans as a cash dividend, the Climate Leadership Council said it should be palatable to Republicans and Democrats in Congress, President Donald Trump and the American public. It’s not about more regulation; as envisioned, it would mean less. It’s not about more tax revenue for the government to spend. It is about free market principles.

The council highlighted a January 2017 report from the U.S. Treasury Department. It determined a carbon tax and carbon dividend would be a financial net positive for about 70 percent of Americans.

The carbon tax contemplated by the report’s authors would exclude “aviation fuels used in foreign trade, a designation that includes international flights.”

An official at the International Air Transport Association also assumed the new proposal would directly impact only domestic U.S. industries. “As a general comment,” according to the official, “aviation is not against paying for our emissions and we have come to the conclusion that an offsetting scheme is the most efficient way for aviation to do so, as in last autumn’s historic agreement at the International Civil Aviation Organization to implement a market-based measure.”

American Airlines and Southwest Airlines indicated that Airlines for America speaks for them on this issue. In an emailed statement, a spokesperson for Airlines for America also pointed to the ICAO approach:

“Airlines are proud that our business model aligns with environmental interests and doesn’t need a carbon tax to further build on our exceptional environmental record. U.S. airlines continue to address aviation carbon emissions through a wide array of technology, operations and infrastructure measures. The global market-based measure agreed to at ICAO will complement those efforts, in addition to a robust effort to bolster the development and deployment of alternative aviation fuels. As part of a global aviation coalition that successfully advocated for the historic ICAO agreement, airlines remain committed to leading the way toward a more environmentally friendly future and will collaboratively work with the Administration and Congress to that end.”

Called the Carbon Offset and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA), the ICAO program is scheduled to start in 2021 with a voluntary phase. It would become mandatory five years later as part of an effort to achieve carbon-neutral growth. Sixty-five nations pledged to take part in the initial phase, including the United States.

It’s no certainty that the United States will stick to its commitment. Trump has shown no hesitation in pulling the country out of international agreements. His skepticism about climate change is well-known. The United States’ participation in the landmark Paris climate agreement, which unlike CORSIA counts domestic aviation emissions, appears in jeopardy.

Climate Leadership Council founder and CEO Ted Halstead said Paris accord commitments are “as we know, very much in doubt.” Baker said the Paris agreement is “not a treaty” and there is no penalty for withdrawing.

Halstead and team are challenged to convince Trump that their plan is sensible. Trump last May tweeted his opposition to a carbon tax.

“For too long, we Republicans — and conservatives — haven’t occupied a real place at the table during debate about global climate change,” Baker said last week. “I was and remain somewhat of a skeptic about the extent to which man is responsible for climate change. But the risks are too great to ignore. We need some sort of an insurance policy.”

They may have a sympathetic ear in new Secretary of State and former ExxonMobil CEO Rex Tillerson. Tillerson during his Senate confirmation hearing last month said he favors a simple carbon tax over “the hodgepodge of approaches that we have today.” He qualified that by saying a carbon tax must be “revenue-neutral,” meaning “none of the money is held in the federal treasury for other purposes.”

The carbon tax concept has plenty of detractors and proponents. Former U.S. Department of Labor chief economist Diana Furchtgott-Roth doesn’t see it flying. In an opinion column published Monday by Investor’s Business Daily, Furchtgott-Roth suggested Trump won’t “be fooled” by the “cleverly” crafted carbon dividend smokescreen. All the proceeds are unlikely to be returned to the American people, she argued. Some would find its way to special interests in Washington. The result of any carbon tax, she concluded, “would be an additional tax, without the offsets that make it so attractive to academics.”

Ian Lipton, president and COO of greenhouse gas tracking firm The Carbon Accounting Company, welcomed the Climate Leadership Council proposal. “Without putting a price on carbon pollution, the market cannot operate efficiently,” he told The Company Dime in an emailed statement. “At present, carbon is not factored into the true cost of production in the United States, and therefore the market is not a ‘free market.’ ”

Also a member of the GBTA Sustainability Committee, Lipton said he “particularly” likes the proposal’s import levy on products from countries lagging in environmental performance. That would protect domestic U.S. manufacturers from a competitive disadvantage.

“Whether the way to go is via a carbon tax or a cap-and-trade system is debatable, but at least they are recognizing the cost of carbon pollution on the planet and on society as a whole,” Lipton wrote. “The real question now is what should be the level of taxation. Some say that level should start no lower than $40 per metric ton and should gradually increase to over $100 per ton. Otherwise, the tax will be insufficient to cause meaningful change. I agree.”

Blogging for the World Resources Institute, climate economist Noah Kaufman called the Climate Leadership Council plan “well-thought-out and ambitious.”

“This tax-and-dividend approach would be highly beneficial to poor and middle-class households, who would receive far more in dividends than they would spend on the tax,” Kaufman wrote on Feb. 10. He noted “strong support” for carbon taxes from the American public and business community.

A carbon tax proposed for the state of Washington would have been the first in the United States, had voters in November not rejected it.

Canada already has started down the path, both on the national and provincial level. Alberta on Jan. 1. began levying a carbon tax on various fuels. It covers jet fuel but only for flights within the province. British Columbia has a similar tax.

Canada’s number two carrier, WestJet, in November said the Alberta carbon tax would cost C$3 million, on top of the C$60 million it already pays in yearly provincial and federal fuel taxes. A national tax in Canada could cost another C$70 million, “all of which we would work to pass through ticket prices,” according to WestJet CEO Gregg Saretsky.

Additional info: Trump met with U.S. aviation leaders last week. They did not discuss the environment, according to a 3,400-word transcript of a 20-minute portion of the meeting. An Airlines for America statement following that meeting mentioned emissions once, as they relate to air traffic control modernization.

The Climate Leadership Council website notes “competing agendas” on climate change around the world. It suggested that the European Union spent 11 years on the “failed Emissions Trading System that has crashed twice and missed its objectives.”

The European Commission just last week proposed to continue the aviation portion of ETS, and to keep the scope to flights within the European Economic Area. EC shelved earlier plans to include flights in and out of EU airspace.